Wildfawn SEO Web Crawler

What is wildfawn?

Wildfawn (stylised “wildfawn”) is an open-source, lightweight SEO web crawler designed to efficiently collect and analyse a website’s core technical metrics. Built with ease-of-use in mind, the application is structured into wildfawn Cloud, an executable which can be configured to automatically schedule and export site crawls, and fawnbot, the standalone crawler and package responsible for all import, crawl, and export processes.

When I first learnt about web crawlers in 2023 through my work in search engine optimisation, I was intrigued to know what was going on behind the scenes, more specifically, why a theoretically straightforward process could sometimes take hours to complete. Although I was keen to learn more, it wasn’t until I’d stumbled across the beautiful Golang, a language practically born for web interfacing, that I sensed a great opportunity to hit two fawns with one stone and learn Go and web crawling together.

Thanks in no small part to my time spent on Advent of Code, whose subtle lessons on Data Structures and Algorithms introduced me to a suite of techniques that you’ll find in this project, I was able to cook up a simple prototype one Friday evening, and the rest is history!

No fawns were hurt in the development of this project.

Features of wildfawn

The core workflow of the crawler is simple:

- Given a single URL, parse its HTML to extract all URLs of the same site.

- Push discovered URLs onto a queue. Avoid recursion, just in case™. Learnt that one in Advent of Code.

- Track which URLs are already crawled. Don’t crawl twice.

Beyond that, I’ve steadily added features and data collection processes to the crawler, including:

crawler.go

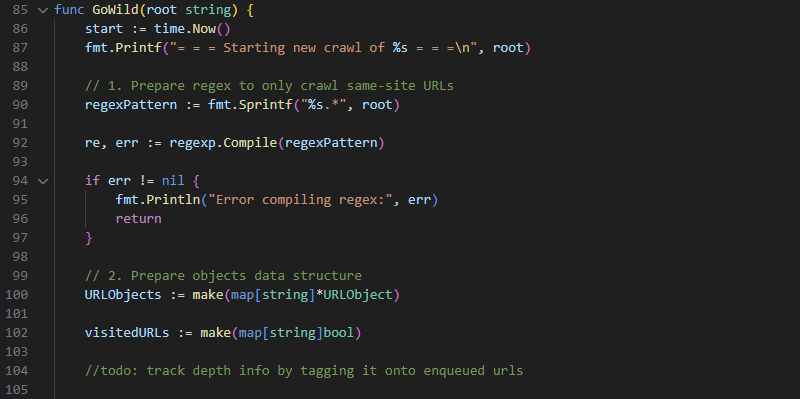

Perhaps the most crucial component of fawnbot, crawler.go handles the queuing and sending of all HTTP requests to the target site, and the parsing of returned HTML and status codes. The entry point is the external method GoWild(), which takes a crawl config containing the root URL, and a program config containing general program instructions.

First, GoWild() resolves the www. preference of the root URL, to which all enqueued URLs will be adjusted as necessary. Most websites today automatically redirect their URLs to one format or the other, but in testing this added a lot of bloat to redirects in the export, obfuscating real issues.

Next up, the function fetches the website’s robots.txt file and parses it into a struct. Go’s lack of classes finally brought me face-to-face with this data type, although in earnest there isn’t much reason for why I hadn’t explored them sooner. Perhaps that’s the fallacy of OOP.

Reading robots.txt is a critical step towards enabling several of the more advanced SEO metrics collectable in a site crawl, and warranted its own collection of relevant functions in robotsManager.go.

The following step is to crawl the site itself, deferring to the internal function crawl(), which uses a queue and a makeshift set to crawl all discovered URLs and ignore already-crawled pages entirely. If robots.txt is respected at this stage (configured by the user) fawnbot will not crawl any disallowed URLs.

To the veteran web scraper, perhaps it is obvious that a queue is the most suitable data structure for this challenge, but for those less inclined I would like to briefly touch on this decision. Recursion is a powerful addition to the developer’s toolkit, and yet I generally make a conscious decision to avoid it in my work. Beyond the clear risk of exceeding the maximum call stack, my many hours solving Advent of Code puzzles has taught me that recursion struggles with scalability, is inherently complex, and unless you’re very careful with passing data through methods, it is highly prone to human error.

In wildfawn specifically, there are further reasons why an alternative solution makes sense. By employing a queue, I can traverse the target site breadth-first, tracking the crawl-depth of pages (as long as no http requests are refused). Using Go’s equivalent of a set, I can dynamically ensure no URL is fetched or crawled twice, eliminating all program overhead.

The crawl() function fetches and parses all HTML, then returns to GoWild() a list of URLObject structs containing SEO-relevant metrics for every URL found in the crawl. A receiver function runPostCrawl() is called on the list to populate any metrics not collectable until after the crawl, before the data is sent back to wherever GoWild() was called from.

robotsManager.go

The robots.txt file is a standardised set of instructions that lets willing crawlers know which parts of a given website they should or should not crawl. It consists of a list of User Agents and Sitemaps, and a semi-supported Crawl Delay, which allow web crawlers to operate under a set of voluntary restrictions. The keyword here is voluntary - there is nothing to prevent web crawlers from ignoring these requirements - but the largest corporate crawlers generally do.

The first parameter, User Agent, is used to provide instructions to specific crawlers, such as to Googlebot or AhrefsBot. It will be followed by lists of paths which can be disallowed or allowed. A website might, for instance, request that crawlers do not send traffic to its purely functional pages.

The next parameter, Sitemap, allows the website to list paths to any sitemaps, to facilitate the discovery of pages on the site.

Lastly, Crawl Delay, while not observed by Google, instructs willing user agents to wait a set amount of time between requests to ease server load.

Aside from parsing robots as a gesture of good faith (wildfawn users can opt to respect it via the program config), there are some vital SEO benefits to including this process in the crawler, too:

- Sitemaps can be used to identify any orphan (unlinked) URLs, that would otherwise not be found through link traversal.

- Conversely, sitemaps can be checked for non-existent URLs.

- Identifying non-indexable URLs or entire folders caused by robots.txt blocking.

analysis.go, postcrawl.go

Many of the metrics wildfawn collects can be collected and calculated as the crawl happens, but there are others (such as total URLs within a category) that can only be calculated post-crawl through an analysis of the data. The analysis.go and postcrawl.go files are designed to serve that purpose, executing after a crawl completes to provide both a summary of the crawl, and the collection of more nuanced metrics.

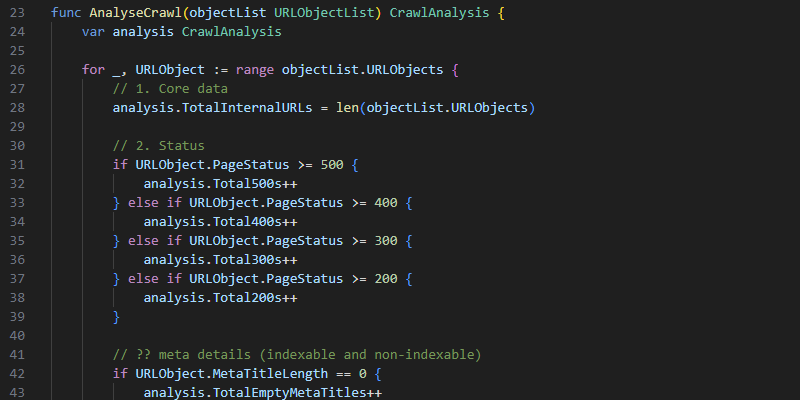

The analysis.go file handles all functionality for producing a separate analysis output of the crawl, used to give the user a top-down view of the technical SEO of the crawled site. A Crawl Analysis struct stores totals for internal URLs (URLs on same domain), URLs with each status code, URLs with empty title and meta description fields, URLs without canonicals, URLs with explicit no-index tags, URLs not in sitemaps, URLs in sitemaps but non-indexable (i.e., URLs that don’t belong in sitemaps), and orphans (URLs with no internal links, necessarily in sitemaps).

Similarly, the runPostCrawl() function in postcrawl.go calculates the remaining values for each URLObject struct for any metrics that cannot be processed on the Go. These are generally bool values: IsOrphan; IsOnSitemap; IsCanonicalIndexable; IsSelfCanonicalising.

import.go, export.go

While not required for the crawl and analysis functionality of wildfawn, the import and export files are intrinsic to wildfawn’s utility as an accessible crawler. They are primarily designed to interface with the Google Sheets API to send and receive information on what sites to crawl, any settings, and a completed export of the results.

The import.go file declares two structs for the program: a ProgramConfig to adjust settings at the application level, and a CrawlConfig to adjust settings at the crawl export level. Most code in this file is self-explanatory, but I’ll briefly point out the IsSiteDue() function, which is used at the package level as part of a process to enable automated scheduling of crawls.

The export.go file is slightly more verbose, and handles the export of data to Google Sheets. Managed from WriteWild(), the function accepts both a list of URLObject and a CrawlAnalysis as data to write, and a CrawlConfig to establish where to write it. A new Sheets Service is set up to enable access to the Sheets API, which uses a local file for authentication (one could just as easily use a secret should this be deployed remotely), and then the function writes the Analysis, the latest Crawl which overwrites the previous crawl, and a copy of the latest crawl should the user wish to keep old data.

Technical thoughts and time complexity of a web crawler

I wanted to comment on several incidental learnings from this experience, especially given that this was my first practical application of the Go programming language.

First and foremost, I gradually added a variety of semantically Go-esque features as I became familiar with the language. Errors as values is a contested feature of Golang, especially to its detractors, but for my own purposes and at the scope I use it, it’s been fun to explore. I hold that the best programming languages are the ones that minimise human error, such as through enforced typing and error checking, and it’s true that Go not forcing you to account for errors is flawed, but that doesn’t make it unusable. It could always be worse - you could be writing your web server in JavaScript or Python. Once I had learnt to handle errors with all the necessary boilerplate code, I still had a program that could return helpful error messages at all failpoints in its codebase.

In a language without native classes, earlier versions of my project tended towards using lots of pointers. In wildfawn, I finally had a use-case for them, and I got to understand what they were for. This no doubt spurred my hot take that pointers are a hack to let you use value types as reference types. But as my codebase grew I soon realised that passing all these pointers around felt a bit overkill for such small objects, and I slowly reverted to using value types where possible.

Receiver functions are Golang’s answer to dot notation, and one of my favourite quality of life features of languages like JavaScript. Even though a functional approach would encourage an expression of the form qux(baz(bar(foo))), the use of dot notation is an example of where human-readability should take precedence in syntactical decisions; the code foo.bar().baz().qux() is so much more digestible. That being said, to include receiver functions in wildfawn I more-or-less had to shoe-horn them in.

There are several practices in wildfawn that I knew to deploy thanks to my time delving into the coding puzzles of Advent of Code. Memoization, an equivalent exchange of computation for memory, is essential to prevent any recrawling of pages on a site, and an understanding of stacks and queues enabled me to design my program efficiently from the outset. Graph traversal led me to crawl breadth-first.

What’s next for wildfawn?

There is a whole world to explore in web crawling and the future is bright. Where do I even begin?

Improved crawl depth

An interesting metric made possible from breadth-first crawling is crawl depth, but this only works as long as the server doesn’t send any 429 ‘slow down’ response codes. Currently, any refused requests (which would need to be recrawled) would make it possible for as-you-go crawl depth tracking to become inaccurate.

Collection of internal links

Naturally, a large part of web crawling for SEO is the collection of internal links, which wildfawn doesn’t currently collect to stay light.

Standalone application

Around my other projects, I am currently developing a full standalone desktop application, which uses a Svelte frontend and function calls to a fawnbot backend. We’ll see how soon I can get this off the ground!